05/12/16

Harold Haizlip, Nora Gregory, and Eugene Wilson

After my research, I can confidently assert that the Dunbar-Amherst Connection sustained itself through an intergenerational cycle of motivation and matriculation in which older generations of Dunbar-Amherst men encouraged younger generations of Dunbar men to attend the College. But is the story of Dunbar and Amherst really that simple? Since I started this research project, I hoped to encounter evidence of how Amherst College might have made an intentional effort to recruit Dunbar students, but finding the right primary sources proved to be somewhat complex. If I could do it over again, I certainly would have spent more time searching for primary sources that could reveal how admission deans were not only aware of the Dunbar-Amherst connection, but strengthened it themselves.

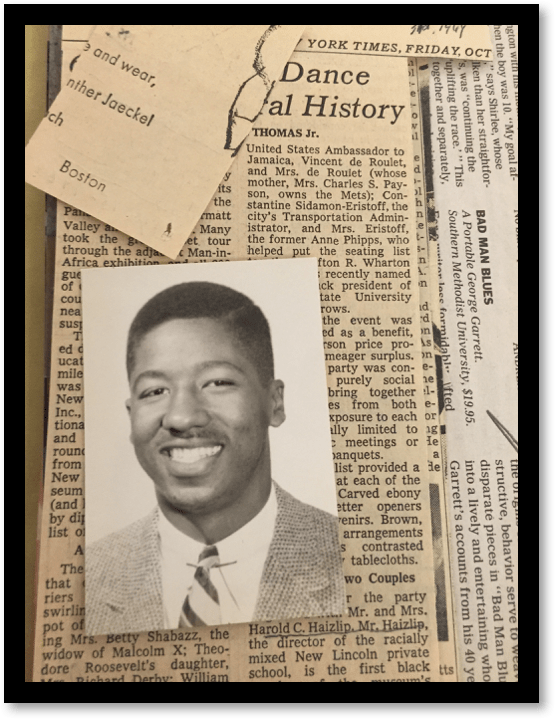

However, I had my second and final phone interview earlier this week with Harold Haizlip ’59 (I interviewed Raymond Hayes ’59 earlier this semester) and I learned how far one admission dean in particular went to reach out to men at Dunbar. Eugene Wilson (1905-1981), starting his career at Amherst’s Office of Admission in 1946 and retiring in 1972, brought a holistic approach to the college admission process as well as a belief in the importance of a diverse student body. One journalist writes that Wilson accepted the admissions post “on the condition that the college set no racial or other kinds of quotas for the students being enrolled (The Amherst News, February 26, 1981).”

In an excerpt from our conversation below, Haizlip remembers how Nora Gregory (the sister of a notable Dunbar-Amherst man, Charles Drew ’26) invited him to her house to meet Office of Admission Dean Eugene Wilson who was visiting Washington, D.C. From his story, it is clear that more than the aforementioned Dunbar-Amherst alumni network motivated Dunbar men to attend Amherst. My theory of the intergenerational cycle of motivation and matriculation should have included more than just the Dunbar-Amherst men themselves. Not just older Dunbar-Amherst alumni, but family members, friends, and even Amherst deans themselves were invested in the Dunbar-Amherst tradition. Clearly, those black Washingtonians connected with Dunbar like Nora Gregory in knew of the success achieved by those Dunbar men who studied at Amherst throughout the early twentieth century. Many prestigious colleges accepted Haizlip and he knew he would attend a northern institution, but the influence of others led him to choose Amherst:

“Her name was Nora Gregory…[she] was Charles Drew’s sister. She was my 5th grade teacher in Washington D.C. I remained in touch with her. She said many times over that you need to go to Amherst College. One day, she called me to meet her at her home…I, of course went…she was very supportive of me…my father had died, I had a difficult time growing up, anything she asked me to do I always did…[There was a] very nice white gentlemen Eugene Wilson…he was the admission dean [of Amherst College]… I had been accepted at Harvard, Yale, Amherst, Williams, and Dartmouth…I knew I was going to college, I didn’t know which one. After that…I made my decision to go to Amherst. He was very honest with me…He could see whether he could help…I could not get a room for race reasons [for] my girlfriend at the time also from Dunbar, a class behind me (Class of 1958) stayed at Dean Wilson’s house for three or four days…That was 1953 I think.”

“He was especially warm and welcoming when recruiting but also after students had made a decision to attend Amherst. He called me in for meetings to discuss whatever was on my mind, whether I was having any problems or challenges, how my academic work was going…A wonderful man, I really liked him a great deal.”

“The admission officers were aware of the students that they were preparing for college…there he was at my fifth grade teacher’s house…the dean of admission! there was quite a history [of the Dunbar-Amherst connection]! I feel like I benefited from that history. There were reasons for the relationship [between Dunbar and Amherst]. There was a positive relationship. This was at a time when it was unusual for college administrators, and white college administrators, to be so aggressive…they knew they were only going to take two…so they went the extra mile to find the best two. I’m sure they knew Nora Gregory’s lineage. It was her son who became the first African-American astronaut, Frederick Gregory. He was a nephew of Charles Drew. His mother who was so instrumental in making sure that I was aware of Amherst and that you had applied for admission.”

-Harold Haizlip, ’57 (excerpted from a phone interview conducted on 05/10/16 by Matt Randolph ’16) (in response to the question- “What specific factors encouraged you to attend Amherst College?”) (The photo is from the Amherst College Archives and Special Collections and features a picture of a young Harold Haizlip ’57).

Research Process

My research incorporated information and images gathered from “bio-files” (every student who attends Amherst College has a file that can be requested from Amherst College Archives and Special Collections). In addition to the standard Amherst College records which provide basic details like residence and relatives, a bio-file could contain an assortment of newspaper clippings and even funeral pamphlets. Even if you don’t find too much, a bio-file can springboard you to further sources of information. The Olio, Amherst’s yearbook, not only helped me put faces to names, but it also helped me understand what extracurricular activities and student organizations the Dunbar-Amherst men participated in during their time at the College.

If you want to research Amherst College alumni, I highly recommend that you start with bio-files and yearbooks. The Higgins Room in the Archives contains an original copy of every single Olio and there are also digitized versions available through ACDC (Amherst College Digital Collections). My most important secondary sources included the two foundational texts for this special topics course (Black Men of Amherst by Harold Wade; Black Women of Amherst College by Mavis Campbell) as well as First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School by Alison Stewart and The Dunbar Story (1870-1955) by Mary Gibson Hundley.

I have also deeply appreciated the opportunity to interview a couple of the Dunbar-Amherst men still living today for my research project. Of course, the capacity to do an oral history project depends on the chronological scope of your research. Even though many of the Dunbar-Amherst men had passed away, I was able to connect with some of the men who we’re at Amherst in the 1950s and still living today. Most alumni are more than happy to share their stories if you reach out to them by email. You can typically find up-to-date contact information for alumni through the College’s Alumni Directory. Just make sure that you have clear and specific questions for them! Although it is important to be mindful of an inherent degree of unreliability with oral history, what I learned from these conversations has been incredibly enlightening and gave me a greater appreciation for the Dunbar-Amherst story in a way that written documents never can.

Final Words

Why does my research on the Dunbar-Amherst connection matter? For the institutional history of both Amherst College and Dunbar High School, as writer Evan Albright puts it, this story that I am exploring is important because “Amherst College graduated more Dunbar students than any other college outside of the nation’s capital (“A Slice of History”, Amherst College Magazine, Winter 2007).” The Dunbar High School of 2016 is quite different from the Dunbar of the early part of the past century but the school is trying to return to its glory days and Amherst could be a critical partner in this process. I would love to see the Dunbar-Amherst connection revived and reimagined in the twenty-first century, perhaps one day through a scholarship program to intentionally bring Dunbar students to Amherst so that they can learn about the historical relationship between the institutions and consider the prospect of attending a liberal arts college like Amherst. I intend to correspond with the Amherst College Office of Admission as well as Dunbar High School itself so we can gradually reach such a goal. A first step could be recruiting some of the brightest students from Dunbar to one of Amherst’s annual Diversity Open House weekends this fall.

However, this research should matter to the student body at Amherst College as well. We cannot fully understand our problems on campus in the present unless we look back to the past. The Dunbar-Amherst Connection reveals the historic importance of structures of support for students of color. Some Dunbar-Amherst men enrolled at Amherst as part of a cohort with one or two other students from their graduating class at Dunbar (or at the very least, they knew Dunbar-Amherst men already at the college and/or in the alumni circle). Administrators who cared about black students also helped to ensure their success, stability, and comfort at Amherst. In reflecting on his college years in the 1950s, Haizlip recalls how Wilson “called me in for meetings to discuss whatever was on my mind, whether I was having any problems or challenges, how my academic work was going.” Wilson was a white admission dean but still did his best to make Amherst a welcoming environment for Haizlip.

I firmly believe that supportive mentors are essential to retaining diversity in higher education after qualified students of underrepresented backgrounds arrive on campus. What was true in the 1950s is true today. In the twenty-first century, students of color still need culturally competent and supportive administrators and faculty members, regardless of their racial and ethnic backgrounds. Without the support of Dean Boykin-East during my first year (and later the guidance of my academic advisor Vanessa Walker), I don’t know if I would be writing this reflection today as a senior at Amherst, with almost a week left before graduation. During my first semester at Amherst, Dean Boykin East gave me an academic planner and advice on how to succeed in my classes. More importantly, she made me feel like I belonged at Amherst and that I had both the potential and the right to thrive here.

I encourage future generations of Amherst students not to shy away from merging the personal and the academic spheres. Some of the best scholarship can come from tapping into our own stories and lived experiences. When we feel personally connected to our research, we develop a drive and passion that empowers us but also inspires others in our communities. With a grandfather who graduated from Dunbar in 1943, this research has been instrumental in learning a little bit about his story and connecting more with my own family’s past. And, although my grandfather never graduated from college, I find it beautiful that in some way we have our own Dunbar-Amherst connection, even if it took a couple generations. My Dunbar grandfather will live to see the day when his grandson graduates from Amherst College this May.