04/07/16

My research of the Dunbar-Amherst connection has certainly taken me outside and beyond the Amherst College Archives recently. In March, I had the opportunity to interview one of those Dunbar Men of Amherst from the “Trio of 1959,” referenced in my previous research reflection.[1] Through email correspondence and over the phone, I interviewed Raymond Lewis Hayes (Amherst ‘59) to discuss his memories as a high school student at Dunbar and an undergraduate at Amherst. Hayes, who trained as a medical researcher and an anatomist, currently resides in Silver Spring, MD but also spends half of the year in Woods Hole, MA. He confirmed that the other two graduates from Dunbar from his Amherst College year were more than just classmates:

“Larry, Bob and I were very close friends. We grew up in the same neighborhood in Washington, DC, were all interested in science and medicine and were encouraged by the opportunity to attend Amherst together.”

In my last reflection, I explored the dynamic of Amherst alumni perpetuating the cycle of the Dunbar-Amherst connection through mentorship of Dunbar students considering elite colleges. My suspicion that previous Dunbar-Amherst men actively encouraged Dunbar students to apply to Amherst too was confirmed by Hayes’s response to my question about factors that influenced his college decision:

“I was recruited and positively influenced by Chauncey Larry, Percy Barnes and Montague Cobb, all black alumni from Amherst and friends of my family. My visit to the college positively reinforced my choice of a small liberal arts college, thus leading to my decision to attend Amherst.”

Unfortunately, through the phone interview, I learned that one member of the trio, Robert Stewart Jason is currently deceased. Jason lived two blocks away from Hayes when they grew up together in D.C. He became a radiologist and was a member of the same fraternity as Ray at Amherst (Kappa Theta).[2]

I was also surprised when Hayes informed me that there was a lack of a politicized identity around blackness in the 1950s at Amherst. I learned that the nature of race relations at Amherst between 1955 and 1959 (when the trio in question attended) differed quite a bit from the post-civil rights movement black experience at Amherst and beyond. Hayes told me that having his fellow Dunbar men at Amherst served as a “built-in advantage” upon arrival on campus and a “fallback of support if we were to need it.” Yet, there were still no black student organizations at Amherst at this point (perhaps they were not deemed necessary at the time?). Indeed, the 50s at Amherst was a time before the Black Student Union of today and the Afro-American Society of the 70s. Of course, Hayes, Burwell, and Stewart likely encountered racism on campus and in the Amherst community but the 1950s were the calm before the storm of radical racial politics of the 1960s and 1970s which would lead to the creation of the Amherst College Afro-American Society, The Gerald Penny Memorial Black Cultural Center, and the Black Studies Department, all three of which were institutional novelties at Amherst that reflected societal changes unfolding throughout the entire nation.

After talking with Steven Kalt ’16, a tech wizard friend of mine, I realized that I need to challenge myself to think about my data differently as I continue with this special topics course and begin developing theories for a final research project. I have been so incredibly focused on completing biographical data entries in my spreadsheet of Dunbar-Amherst men that I forgot to consider my findings in the context of the black community at Amherst in general.

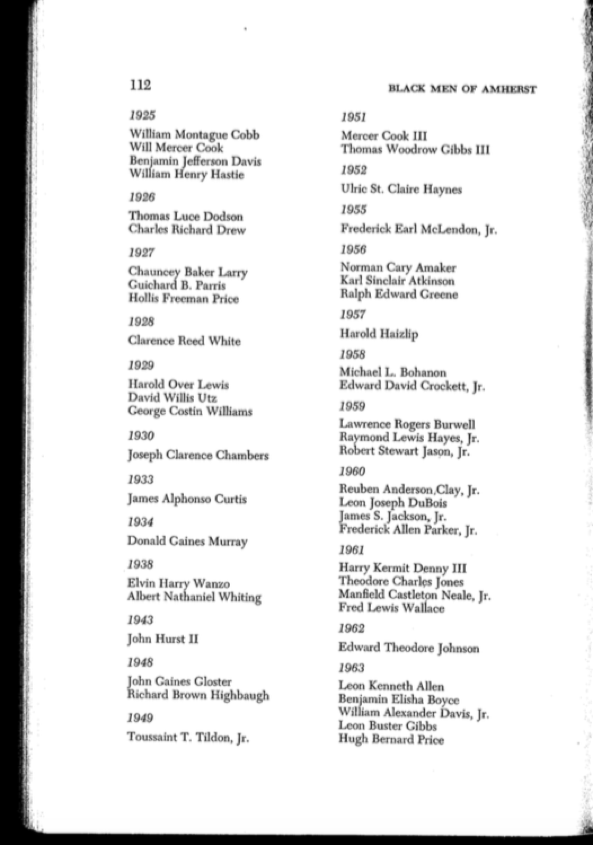

What was the ratio of Dunbar men to those blacks who graduated from different high schools? In the 1910s and 1920s? In the 1940s, 1950s, etc.? Was there ever a year in which Dunbar men made up a notably large population or majority of the black community at Amherst? What has been the black faculty/staff to student ratio since the turn of the twentieth century when the Dunbar-Amherst story began? To begin to answer such questions, I turned to the appendix of Black Men of Amherst by Harold Wade, this course’s foundational text. As you’ll see from the image of page 112 of the appendix, the “Trio of 1959,” a group of graduates from Dunbar, comprised the entirety of the black population in their class according to Wade’s research. Additionally, for the class of 1925, three-fourths of the black students are Dunbar men (Davis is the only exception). In 1926, Drew and Dodson, both from Dunbar, were also the only black graduates in their Amherst College class.

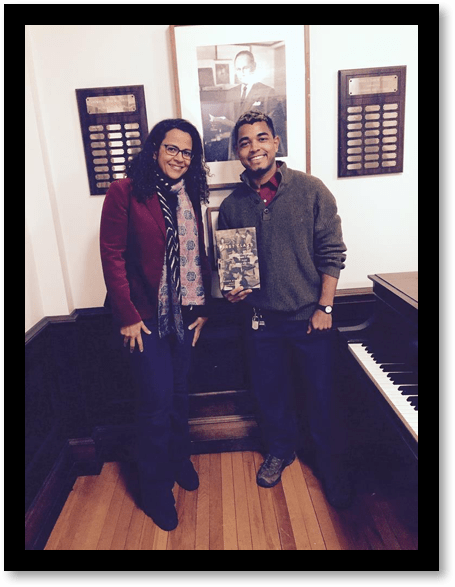

On behalf of the Black Student Union, I brought journalist and author Alison Stewart to campus this past Tuesday evening to discuss her book First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School (2013). I am incredibly grateful that I was able to gather the necessary funds to make her visit possible through the President’s Office, the Office of Student Life, and the Association of Amherst Students. The Multicultural Resource Center also covered the cost of a delicious catered meal from Pasta e Basta. The dinner was held in The Gerald Penny Memorial Black Cultural Center of the Octagon and served as an opportunity for a select group of faculty, staff, and students to get to know Alison on a personal level. Alison gave an eloquent and engaging speech about the Dunbar story that reinforced my confidence in the importance of historical knowledge for engaging with the world today. I hope the other students that attended also left with a heightened appreciation for the Amherst alumni that came before them who led lives of consequence, leaving legacies for us to admire and emulate. From the photograph, you’ll see that I had a chance to tour Alison around Charles Drew House (my dormitory as a junior)!

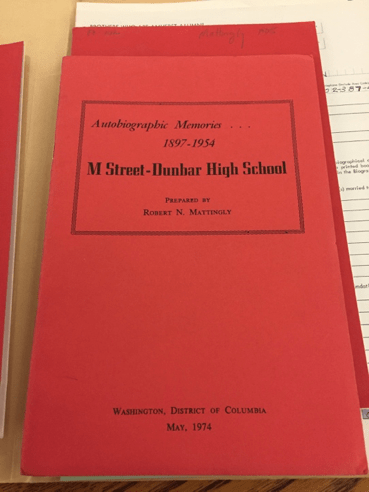

I appreciated how she tailored her speech to our college community, spotlighting the many alumni of Dunbar who matriculated at Amherst. In the next week or so, I’m hoping to take a closer look at the bio-file of Robert Nicholas Mattingly, technically the first Dunbar-Amherst man (’02, ’06).[3] In her speech, Alison referred to Mattingly and emphasized how he returned to D.C. to become the principal of Cardozo High School. In one document from his bio-file, “Autobiographic Memories, 1897-1954: M Street-Dunbar High School,” prepared by Mattingly himself in 1974, there is a list of Dunbar-Amherst men! Mattingly writes that “Amherst records reveal that more M Street-Dunbar High School students have graduated from Amherst College than from any other college or university outside of the District of Columbia.” It’s nice to know I’m not the only one who has been curious about the connection between the institutions!

I appreciated how she tailored her speech to our college community, spotlighting the many alumni of Dunbar who matriculated at Amherst. In the next week or so, I’m hoping to take a closer look at the bio-file of Robert Nicholas Mattingly, technically the first Dunbar-Amherst man (’02, ’06).[3] In her speech, Alison referred to Mattingly and emphasized how he returned to D.C. to become the principal of Cardozo High School. In one document from his bio-file, “Autobiographic Memories, 1897-1954: M Street-Dunbar High School,” prepared by Mattingly himself in 1974, there is a list of Dunbar-Amherst men! Mattingly writes that “Amherst records reveal that more M Street-Dunbar High School students have graduated from Amherst College than from any other college or university outside of the District of Columbia.” It’s nice to know I’m not the only one who has been curious about the connection between the institutions!

[1] I discovered that three Dunbar graduates all went on to Amherst together and later became doctors.

[2] Considering the proximity of their homes during their Dunbar years, perhaps a digital mapping project could be a possible component of my final project.

[3] Mattingly is technically the first Dunbar-Amherst man if you don’t count William Tecumseh Sherman Jackson (Amherst 1892), an early principal of M Street High School (1906-1909). He convinced Charles Hamilton Houston, Class of 1915, to apply to his alma mater, initiating the cycle of encouragement for attending Amherst that I mentioned earlier.